Not too long ago, many Yehudim as well as many Christians would have commemorated a significant event that took place in ancient Israel. That event is the Passover.

This was at a time just before Moses delivered the Israelites out of the Egyptian bondage of slavery. The very night when judgement would fall on Pharaoh and his people, God had warned the Israelites to sacrifice an unblemished lamb and use the blood on their mantelpiece.

This was to be a mark to identify themselves as God’s covenant people. As the Angel of Death swept over Pharaoh’s kingdom, he recognized that mark and so his judgement passed over those houses. Every year, the Yehudim would remember this important event in their calendar.

For believers of Christ, the Passover would take on an even more momentous meaning through the Messiah. Recently, Rev Joseph Steinberg of CWI had a series of seminars to explain how the Passover points to the Gospel, giving insights into both its spiritual as well as cultural aspects.

The way the Yehudim prepare for the Passover is much more elaborate than for many of us. Many of them would prepare the house 6 weeks in advance, spring-cleaning it, before culminating in the Feast of the Unleavened Bread (matzah; the Bread of Affliction) that last for 7 days after the Passover.

‘When a leaven enters bread, it gets puffed up and that’s what happens when sin enters into our lives; we get puffed up with pride and rebellion against God,’ Rev Steinberg illustrated. For 7 days, the Israelites would eat only unleavened bread, remembering also how speedily God had brought them out of bondage. God had told them then to immediately pack their belongings and leave the moment God opened the way through the Pharaoh’s stubbornness.

This cleansing process so that the house would be pure on the actual day of celebration is known by the Yehudim as the Bedikat Chametz. On the day of the celebration, the women would hide a pile of crumbs in the house, and the men would search for it armed with a spoon, a feather, and a linen cloth. The men would sweep the crumbs (a symbol of sin) with the feather into the spoon, being careful not to touch it, take it to the synagogue and then cast it into the fire.

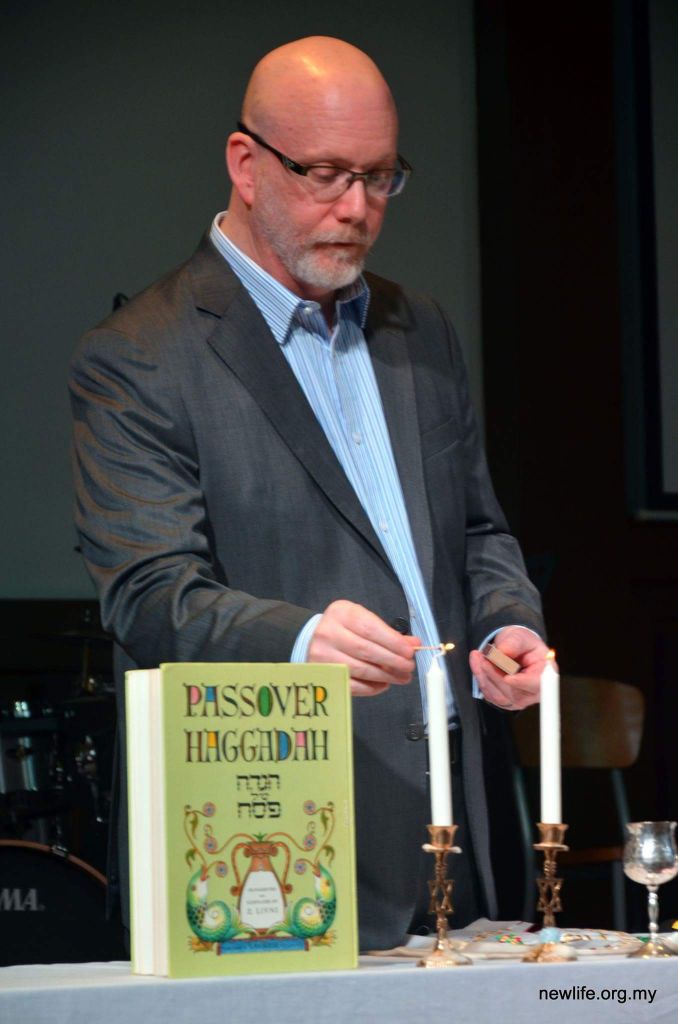

The actual Passover celebration would be done in the house. The story of God’s deliverance would then be told through the Haggadah (the telling). Rev Steinberg communicated that for those who partake of the Passover meal, it is really a liturgy that the partakers eat their way through.

God commanded the Israelites that this episode should be told and remembered for all generations. ‘God never wants us to forget that He is a God who saves. The Passover is an object lesson and everything on the table is a symbol to remind us of a part of the wonderful story of God.’ In Hebrew, the Passover feast is known as the seder which means ‘order’ denoting that there is an order in which it is performed.

The very first thing in a seder must be performed by a woman. The lady of the house lights the candles at the tables and recites a prayer of thanksgiving. ‘So it is through the prayers of a woman that light is brought into the service which speaks clearly of Jesus and it is through the seed of a woman and the will of God that the Light came into the world. Jesus was the only Man not born of the seed of man, thus He fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah (Isaiah 7:14)’.This very first step already echoes the coming of the Light into the world.

On the table there will be four cups, each of which has a special name and significance. The first is known as the Cup of Sanctification. The seder is a meal that is set apart (sanctified), and it is now that the man of the family takes over, raises the Cup of Sanctification, and delivers another prayer of thanksgiving. With the participation of both the women and men, the meal then begins proper.

Each element of the seder(order)plate tells a story. The first thing that is partaken is called the karpas (a vegetable, usually parsley or celery, which is dipped in liquid (usually salt water) and eaten).The karpas is a symbol of life, eaten at the beginning of the meal by the Israelites to remember and celebrate God as the source of life, the Creator who has the power to bring something out of nothing.

The karpas is first dipped into salt water to symbolize the tears of life. The Israelites were supposed to be the light to the world but they were held under bondage. It is also a reminder that a life without the promise of God’s redemption is a life immersed in tears.

The next element is known as the maror (normally freshly-ground horse radish, a bitter herb of a family of plants that include the mustard and wasabi), eaten as a reminder of the bitterness of slavery. There is a story to tell in the maror, explained Rev Steinberg. Like sin, the maror smells sweet and tempting to the senses but as we eat, the bitterness (the pain of sin) becomes very real. Like the karpas it is a reminder of a life without a Redeemer.

The maror is followed by the Charoset (a sweet mixture of cinnamon, apples, walnut, and raisins). But the Charoset in fact symbolizes the mortars that the Israelites used to build the storehouses of Egypt while under slavery. The rabbi would ask the question, ‘Why should such a sweet mixture represent such a hard labour?’ And the answer is because even the harshest labour is sweetened by God’s redemption.

This is the Christian hope, Rev Steinberg expressed. As we work and as we labour through our lives and as hardship come, our lives should be sweetened by the promise of Christ’s imminent redemption for us.

Next is the Hagigah/Beitzah(representing the burnt offerings/sacrifices from the Temple, dipped into the salt water before eaten). To the Israelites, this was a symbol of grief. It reminded the Israelites that after the Temple was destroyed, they lost the sacrifices that brought them peace with God. They lost the ability to have atonement for their sins. Rev Steinberg expressed that many Yehudim work hard to live a life thathonour God, but they do not have the assurance that they’ve been really forgotten and accepted by God. ‘The Passover Lamb is missing and so there is this hagigah but we see the great mystery of God. Jesus was our once and for all time sacrifice.’

Another bitter root, the chazeret, is a reminder that our lives have a bitter root to them. It reminded the people that in Goshen they had a bitter life. For Christians, it reminds us that we’re all wired to a nature that is very quick to do wrong and yet God’s redemption has the power to transform the bitterest life into one that is filled with His sweetness and His peace.

The last thing on the seder plate is the zeroah (the shank bone of a lamb). The shank bone reminds us of the lamb that was slain at the Passover. ‘You and I know that God was not caught off-guard when the Temple was destroyed. We know God’s great mystery that the Lamb of God, Jesus, came and that at Passover He sacrificed for us once and for all time, even 40 years before the Temple was destroyed.’

‘As I have been explaining Passover for many years, there is something that has become clear to me over these years. The way the elements of the Passover tell everyone a story, everyone who has the Lord Jesus in their life story,’ Rev Steinberg said.

‘Because like the karpas (symbol of life) we’re born into this world with lives and yet our lives from the beginning, even before we came out of our mother’s womb, are immersed in tears. Because of sin in our lives that separated us from God (maror; symbol of the bondage of sin) and so the Lord God comes to us to reconcile us to Himself.

‘He does it through the sweet Saviour (charoset; the light in the bitterest of hardship), the One who gave His life as a sacrifice (hagigah; symbol of sacrifice), in order to take the bitter root from our lives (chazeret) and make us one with the Lord. Because Jesus is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world (zeroah; the Passover Lamb).’ In one seder plate, the whole story of the Gospel is encapsulated.

But the Gospel in the Passover goes deeper than even the elements of the seder plate. There is the blood of the sacrificial lamb on the lintel and door posts (forming a cross) during the First Passover for example.

Although a night of salvation, the second of the four cups (the Cup of Affliction) reminds the Israelites and us that one cannot be completely joyous when some of God’s creatures had to suffer. With the recital of the Ten Plagues, each participant removes a drop of wine or curse from his or her cup using a fingertip.

Rev Steinberg imparted that while many people have accused God of favouritism, it was not an issue of Hebrew versus Egyptians. It was a matter of the obedience of the heart. God had to bring ten plagues to Egypt before the Pharaoh would listen. Moses had warned the Pharaoh of what would happen at the tenth plague. Everyone in the kingdom would have known what was coming.

God had given the command to sacrifice an unblemished lamb, and to use its blood as a mark against the mantels of the house, and then to bring the sacrificial lamb into the house and inside them. Everyone who obeyed were spared and the Bible records that there were some Egyptians who followed the Israelites out of Egypt (Exodus 12:48).

In the New Covenant, a Christian is someone who decides to follow Jesus and allows Him to change their hearts. Like the Israelites in this story, a Christian is someone who lives by faith; someone who has applied the Blood of Jesus to the doorposts of their heart and asks Jesus to come in to become Lord and Saviour of their lives. So that when we stand before God at the end of time and His judgement comes before us because all have sinned, if we have the Lamb’s blood cross, the judgement would pass over us.

Rev Steinberg imparted that this must be a reminder to all of us that we must trust in the Lord Jesus; that all people must trust in the Lord Jesus. Jesus paid a sacrificial price for each one of us, but we must apply Him into our hearts and our lives. Other aspects of the Passover meal including the eating of the afikoman, and the remaining cups (The Cup of Redemption, The Cup of Praise, Elijah’s Cup) encapsulates the Gospel story in its totality.

|Share The Good News|

Jason Law

NOTE: All pictures kindly contributed by the organiser.

Leave a Reply