12 Feb 2014 by Yeo Teck Thiam-

In our schooldays, most of us would have to learn a collection of poems as part of our literature lessons. There were many that were delightful and memorable, and I certainly remember a number of these fondly. Yet there were some that did not quite make much sense — at least, at the time that some pupils, like myself, found!

One of them that stuck in my mind was this poem titled ‘Ozymandias’ by Percy B. Shelley. It is without any doubt, a beautiful poem. But I did not know who the person was, or why Shelley thought so much about him that he composed this poem. And so I found it frustrating, and yet beautiful!

OZYMANDIAS OF EGYPT

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them in the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

1792-1822

Shelley’s poem has to do with a kingdom that now lay in ruins in the sands; and of course, one of the figures in Egyptian or Mesopotamian history was clearly likely. Yet I could not seem to find anyone with this name, or similar names.

I have left it at there, in the classroom, and thought no more of it.

Yet, strangely, in my later years, in learning the rudiments of hieroglyphs, I finally found the answer. The name was a transliteration of ‘Ooser Maat Re’, the name that we know more familiarly as Rameses II, Pharaoh of Egypt.

I could not tell if Shelley knew his identity, but he did choose his subject well! The deciphering of the hieroglyphic script was in its infancy at his time. Jean-Francois Champollion had only just broken the code through his mastery and matching of the Rosetta stone story in 1822, the year that Shelley later drowned at sea in a storm off the coast of Marseilles.

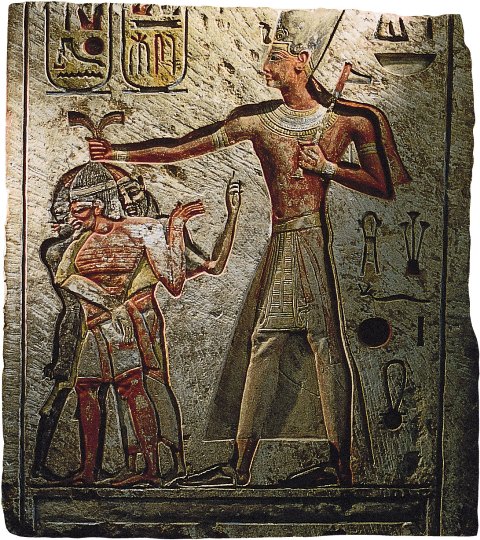

And so the cartouche, the king’s inscription of his name in the stone carving, was read as it appeared. Nowadays, of course, we would read it as “Ra Maat Ooser”, in line with Ramases as we well know.

‘Ooser Maat Re’ meant Ra, the Egyptian sun god, was “ooser” or powerful, and so the man who bore his title was likewise. Maat was the Egyptian goddess of justice, and pictorially gave an equivalent meaning of justice.

The hieroglyph script had no vowels, and scribes who carved royal inscriptions also used different hieroglyphs to spell eloquently the name of the Pharaoh. Thus, in the cartouche also, was this king, powerful and just, for he was flanked on his sides by his god and goddess, Ra and Maat.

Of the Pharaohs of Egypt, Rameses II had one of the longest reigns. He ruled for 66 years (1290 – 1224 B.C.). His expeditions and campaigns were well recorded, since every Pharaoh wished to be well remembered. And so the temple inscriptions, especially at Abu Simbel and Ramesseum in Thebes, left us with impressive and illustrious accounts of his reign.

Rameses II had always been figured as the likely Pharaoh of the Exodus. We do not know with certainty. It is probable, since various circumstantial evidences support this view. But the problems have always been the dates of events.

Unless we have certainty of the Exodus dates, or parallel Egyptian records of the event, it is best to leave it, as it is presently — unconfirmed. No Pharaoh would deem it fit to speak of his failures and defeats. And so, unfortunately, we have mostly the records of the Pharaohs’ victories and achievements.

One of the hopeful trails is the mention of the storehouses of the Pharaoh. In Exodus 1:11, the Hebrews were reduced to a state of slavery, subject to forced labor, and they built Pithom and Rameses.

‘Pr’, or in our equivalent ‘Pi’, means house. Pi-thom and Pi-Rameses were the two cities specifically built to be granaries and store cities. They were in Lower Egypt, that is, in the Delta region of Egypt, where the River Nile forms a massive fertile flat land for agriculture, before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea.

This mention of the store cities does point to Rameses II as the likely Pharaoh, through giving his name to the city. But it is by no means certain, since the Pharaoh could assume the city’s name, even if this was unlikely.

Rameses I who ruled for hardly a year, in about 1304 B.C., did not build these cities, and therefore, did not figure in the Exodus account.

Sethos I (1304 – 1290 B.C.), Rameses II’s father, commenced the building of the two cities, but it was Rameses II who made the cities as we know them.

Be that as it may, Shelley is quite right to say, ‘Nothing beside remains’. Whatever man’s greatness and achievements, the sands of time level all to nothing.

Note: Mr Yeo Teck Thiam is a retireer who used to work as a chemical engineer, specializing in food and perfume chemistry for an international food company and perfumer. His other main interest is astronomy and other mathematical matters, relating to the Biblical passages.

References for pictures

http://wordmusing.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/percy-bysshe-shelley.jpg

http://atomictoasters.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Ozymandias.jpg

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-QDaXpALIXFY/Tc8y7Tm-WSI/AAAAAAAABpM/WAyy8l4gdqk/s1600/Ramses_II-Luxor.jpg

http://ashraf62.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/ramses-ii-relief-from-memphis.jpg

http://www.bibleistrue.com/qna/pithom2.jpg

http://hero026.edublogs.org/files/2011/04/my-beyotchh-28f7l6j.jpg

Interesting.